Fault detection

What is it?

Fault detection is the deliberate act of checking a system, subsystem, or software component for erroneous states and stopping those errors from propagating. It uses value-domain checks (limits, plausibility, monotonicity), time-domain checks (timeouts, deadlines, execution jitter), and structural means (redundancy, diversity, voting). In self-checking systems, a component relinquishes control or triggers a safe state when it detects its own results are incorrect. Fault detection can be implemented at multiple levels: physical (e.g., temperature, voltage), logical (e.g., error-detecting codes), functional (e.g., assertions), and external (e.g., cross-checks against independent measurements).

How it supports functional safety

Fault detection reduces the likelihood that systematic failures—such as software bugs, logic defects, integration mistakes, or incorrect assumptions—will silently propagate to the safety function. By detecting anomalies quickly and activating a defined safe reaction, the design limits the consequence of such failures within the fault tolerant time interval (FTTI). Fault detection also intercepts manifestations of random or common-cause hardware faults when they appear as corrupted values, timing violations, or protocol errors, so the safety function does not act on bad data.

When to use

- When a single, unchecked computation or sensor value could lead directly to a hazardous control action.

- When SIL targets require diagnostic coverage of input processing, control logic, or communication paths.

- When communication links may drop, corrupt, or reorder messages (e.g., fieldbus, CAN, Ethernet).

- When environmental or process dynamics make “stuck-at”, out-of-range, or implausible values credible.

Inputs & Outputs

Inputs

- Critical signals and computed results (sensor values, actuator commands, estimates).

- Timing information (task periods, deadlines, heartbeat/“kick” events).

- Protocol metadata (CRC, sequence counters, timestamps, freshness indicators).

- Configuration for limits, rate-of-change, plausibility rules, and timeouts.

Outputs

- Fault flags and diagnostic codes (latched as appropriate).

- Safe reaction commands (e.g., shut down heater, hold last safe value, switch to redundant channel).

- Degraded/limp-home mode selection.

- Traceable diagnostic records (event logs, counters, timestamps).

Procedure

- Map hazards to checks. Identify signals and computations whose unchecked failure could cause a hazard; derive value-domain, time-domain, and structural checks from the FMEA/FMEDA and FTTI.

- Select detection mechanisms. Combine range/limit checks, rate-of-change and plausibility rules, timeouts and watchdogs, error-detecting codes (e.g., CRC), and—where justified—redundancy with voting or a diverse monitor.

- Define safe reactions. For each detected fault, specify a deterministic, bounded-time reaction (e.g., discard/ignore, hold last known safe value, enter safe state, switch channel) and how it is latched and reset.

- Implement locally. Place checks at the smallest practical subsystem (function/module) to localize diagnosis; propagate only validated data to higher levels with associated diagnostic status.

- Instrument diagnostics. Count detections, timestamp events, and store context with affected data to support trend analysis and investigation.

- Verify & validate. Use unit tests, boundary tests, timing analysis, and fault injection to confirm detection coverage and that reaction time ≤ FTTI; document evidence for assessment.

Worked Example

High-level

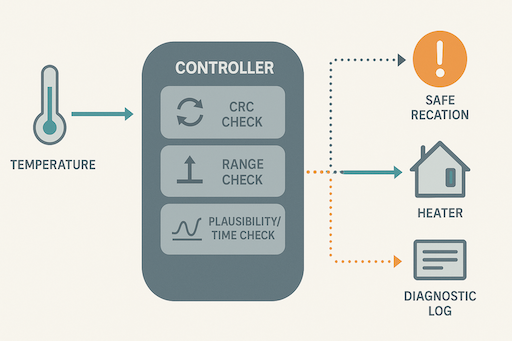

A heater is controlled by a safety controller using a temperature sensor message that carries a sequence counter and CRC. Software implements: (1) CRC check, (2) range limits, (3) rate-of-change and “stuck” detection, and (4) freshness timeout. If any check fails, the controller disables the heater and latches a diagnostic until a supervised reset.

Code-level

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

#define TEMP_MAX_Cx10 1200 // 120.0°C in tenths

#define TEMP_MIN_Cx10 -400 // -40.0°C in tenths

#define MAX_ROC_Cx10 50 // max rise per sample (5.0°C)

#define STUCK_LIMIT 5 // max identical readings before flag

#define FRESHNESS_MS 200 // data must arrive within 200 ms

extern uint32_t platform_millis(void);

extern void heater_off(void); // SAFE REACTION actuator

extern void log_fault(const char*); // traceable diagnostic

extern bool read_sensor_frame(uint8_t* buf, uint32_t len);

static void safe_shutdown(const char* reason) {

heater_off(); // SAFE REACTION: enter safe state

log_fault(reason); // record fault

}

// Simplified example check

bool check_temperature(int16_t new_temp) {

static int16_t last_temp = 0x7FFF;

static int repeat_count = 0;

if (new_temp > TEMP_MAX_Cx10 || new_temp < TEMP_MIN_Cx10) {

safe_shutdown("Out of range");

return false;

}

if (last_temp != 0x7FFF) {

int16_t roc = new_temp - last_temp;

if (roc > MAX_ROC_Cx10 || roc < -MAX_ROC_Cx10) {

safe_shutdown("Rate of change fault");

return false;

}

if (new_temp == last_temp) {

if (++repeat_count > STUCK_LIMIT) {

safe_shutdown("Sensor stuck");

return false;

}

} else {

repeat_count = 0;

}

}

last_temp = new_temp;

return true; // value accepted

}

Result: The controller will not act on corrupted, stale, or implausible data; instead it deterministically disables heat within the FTTI, latches the condition, and provides diagnostics.

Quality criteria

- Timeliness: Worst-case detection + reaction time proven ≤ FTTI.

- Determinism: Checks have bounded execution time and well-defined priorities.

- Coverage: The set of checks demonstrably covers relevant failure modes.

- Independence: Monitors sufficiently diverse to avoid common systematic faults.

- Traceability: Faults, counters, and timestamps are recorded and linked to requirements and tests.

Common pitfalls

- Detection without reaction. Mitigation: Always specify and test a bounded safe reaction.

- Single check syndrome. Mitigation: Combine value, time, and structural checks.

- Non-diverse monitor. Mitigation: Use dissimilar/simple monitors, not duplicates.

- Over-sensitive thresholds. Mitigation: Tune thresholds using real data and add hysteresis.

- FTTI exceeded. Mitigation: Analyze timing, prioritize detection tasks, and pre-emptively disable hazards.

References

FAQ

Does fault detection always require redundancy?

No. Redundancy is one option. Many designs combine simple value/time checks (limits, plausibility, freshness) with protocol checks (CRC, sequence) and a lightweight diverse monitor to achieve coverage with lower cost and complexity.

How is “diagnostic coverage” shown for software fault detection?

IEC 61508 treats DC primarily for hardware, but software detection can prevent unsafe outputs and support the overall safety case. Show evidence via requirements traceability, fault-injection tests, coverage vs. identified failure modes, and timing proofs that reaction ≤ FTTI.

What’s the difference between fault detection and fault tolerance?

Detection finds erroneous states and triggers a safe reaction (e.g., shutdown or degrade). Tolerance continues service despite faults (e.g., hot standby with voting). Many safety designs detect and then either tolerate (switch channel) or go safe.

What evidence convinces assessors?

Documented rationale for checks, independence/diversity argument, WCET/timing analysis, repeatable fault-injection results, and latched diagnostics tied to hazards and FTTI demonstrate adequacy.